Frans de Waal taught the world that animals had emotions

Frans de Waal taught the world that animals had emotions

The young male chimps at Burgers’ Zoo in Arnhem were fighting again. They were running round their island, teeth bared, screaming. Two in particular were battling until one definitively won, and the other lost. They ended up, apparently sulking, high in widely separate branches of the same tree. Then young Frans de Waal, who was observing their wars for his dissertation, saw something astonishing. One held out his hand to the other, as if to say “Let’s make it up.” In a minute they had swung down to a main fork of the tree, where they embraced and kissed.

He did not hesitate to call this what it was: reconciliation. What was more, it was essential if the group was to cohere and survive. The word, though, scandalised his tutors. Studying primates in those days, the mid-1970s, was mostly a matter of recording violence, aggression and selfishness.

Frans de Waal has died. All brings to mind the wonderful photo of the chimp and Jane Goodall eyeing each other up in the Think Different series.

End of science (as we once knew it)

Citation cartels help some mathematicians—and their universities—climb the rankings | Science | AAAS

Cliques of mathematicians at institutions in China, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere have been artificially boosting their colleagues’ citation counts by churning out low-quality papers that repeatedly reference their work, according to an unpublished analysis seen by Science. As a result, their universities—some of which do not appear to have math departments—now produce a greater number of highly cited math papers each year than schools with a strong track record in the field, such as Stanford and Princeton universities.

These so-called “citation cartels” appear to be trying to improve their universities’ rankings, according to experts in publication practices. “The stakes are high—movements in the rankings can cost or make universities tens of millions of dollars,” says Cameron Neylon, a professor of research communication at Curtin University. “It is inevitable that people will bend and break the rules to improve their standing.” In response to such practices, the publishing analytics company Clarivate has excluded the entire field of math from the most recent edition of its influential list of authors of highly cited papers, released in November 2023.

Corporations tend to choose survival over morality in the absence of countervailing power.

The (not so) strange case of Katalin Karikó

The 2023 Nobel prizes – What they mean for higher education

The strange case of Katalin Karikó

Dr Katalin Karikó, joint winner of the physiology-medicine award, has received much comment in the media. Born and educated in Hungary, she has spent most of her career in the United States. But she has also held appointments in three other countries at a variety of institutions, and has most recently been senior vice president at BioNTech, a biotech company in Germany.

The debate stems from her time at the University of Pennsylvania, where she worked from 1989 to 2001, in positions ranging from scientific assistant professor, to senior head of research, to adjunct associate professor.

During that period, she was demoted from a tenure-track position in 1995, refused the possibility of reinstatement to the tenure track and eventually ushered into retirement in 2013.

Meanwhile, her close collaborator and fellow prize winner, Dr Drew Weissman, whom she met in 1997, remains at the University of Pennsylvania as professor of medicine, as well as being co-director of the immunology core of the Penn Center for AIDS Research and director of vaccine research in the infectious diseases division.

Some have pointed out that Karikó was working on risky or unconventional scientific themes, and that the usual funding agencies and senior academics were unable to see the promise in her work until recently, when she and her colleague Weissman have been recipients of multiple prizes. The fact that she received her doctorate from the University of Szeged in Hungary and not a prestigious institution in a major country may not have helped.

None of this story is surprising nor strange.

Roger Searle Payne (1935–2023) | RIP

Roger Searle Payne (1935–2023) | Science

He changed the world. Humanity takes longer to come aboard.

Roger Searle Payne, the biologist who pioneered studies of whale behavior and communication and advocated for their protection, died on 10 June. He was 88. Payne was widely known to both scientists and the public for his groundbreaking discovery of the songs of humpback whales.

Born on 29 January 1935 in New York City, Payne received a BA in biology from Harvard University in 1956 and a PhD in animal behavior from Cornell University in 1961. From 1966 to 1984, he served as a biology and physiology professor at The Rockefeller University in New York. In 1971, Payne founded Ocean Alliance, an organization established to study and protect whales and their environment, and he remained its director until 2021.

Initially, Payne’s research focused on auditory localization in moths, owls, and bats, but he changed course to focus on conservation and selected whales for their status as a keystone species. In 1967, he and his then-wife Katharine (Katy) first heard the distinctive sounds of the humpback whales on a secret military recording intended to detect Russian submarines off the coast of Bermuda. Payne and his collaborators, including Scott McVay and Frank Watlington, were the first to discover that male humpback whales produce complex and varied calls. Mesmerized by the recordings, Payne realized that the recurring pattern and rhythmicity constituted a song. He published his findings in a seminal Science paper in 1971. After many years and many additional recordings, he and Katy further realized that the songs varied and changed seasonally.

These hauntingly beautiful whale songs captured the public’s attention thanks to Payne’s extraordinary vision. He released an album, Songs of the Humpback Whale, in 1970 that included a booklet in English and Japanese about whale behavior and the dire situation that many species of whales faced. He recognized the power of juxtaposing the plaintive and ethereal songs of humpbacks with images of whaling.

The album remains the most popular nature recording in history, with more than two million copies sold. Humpback whale songs are now carried aboard the Voyager spacecrafts as part of the signature of our planet.

The glory of science

The great joy of science and technology is that they are, together, the one part of human culture which is genuinely and continuously progressive.

This is from the science and tech editor at the Economist who is standing down from that role at three decades. Science: Stop and starts — not continuous. And that is just for starters. Discuss!

Hugh Pennington | Deadly GAS · LRB 13 December 2022

Another terrific bit of writing by Hugh Pennington in the LRB. It is saturated with insights into a golden age of medical science.

Streptococcus pyogenes is also known as Lancefield Group A [GAS]. In the 1920s and 1930s, at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, Rebecca Lancefield discovered that streptococci could be grouped at species level by a surface polysaccharide, A, and that A strains could be subdivided by another surface antigen, the M protein.

Ronald Hare, a bacteriologist at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital in London, worked on GAS in the 1930s, a time when they regularly killed women who had just given birth and developed puerperal fever. He collaborated with Lancefield to prove that GAS was the killer. On 16 January 1936 he pricked himself with a sliver of glass contaminated with a GAS. After a day or two his survival was in doubt.

His boss, Leonard Colebrook, had started to evaluate Prontosil, a red dye made by I.G. Farben that prevented the death of mice infected with GAS. He gave it to Hare by IV infusion and by mouth. It turned him bright pink. He was visited in hospital by Alexander Fleming, a former colleague. Fleming said to Hare’s wife: ‘Hae ye said your prayers?’ But Hare made a full recovery.

Prontosil also saved women with puerperal fever. The effective component of the molecule wasn’t the dye, but another part of its structure, a sulphonamide. It made Hare redundant. The disease that he had been hired to study, funded by an annual grant from the Medical Research Council, was now on the way out. He moved to Canada where he pioneered influenza vaccines and set up a penicillin factory that produced its first vials on 20 May 1944. [emphasis added]

He returned to London after the war and in the early 1960s gave me a job at St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School. I wasn’t allowed to work on GAS. There wasn’t much left to discover about it in the lab using the techniques of the day, and penicillin was curative.

[emphasis added]

Confusion will be my epitaph

I entered academia as an established professional musician, and I continue to work as a performer, but my research and teaching are equally centred around traditional academic scholarship, as well as practice outputs. This is unusual; most music practitioners on research contracts primarily pursue practice-based projects (compositions, performances, recordings, multimedia works), outputs from which are submitted to the REF with the near-mandatory 300-word statement setting out why they should be considered research.

And people try and justify the REF. Utterly stupid:SRFM.

(Title: h/t King Crimson)

But they are my own failures

Is the age of ambition over? | Financial Times

Here’s the second thing I learnt: it’s still better to be disappointed by your own dreams than shaped by the dreams of others. Patrick Freyne

Was my own research philosophy. I would rather my own less-than-perfect experiments than be a cog.

How ‘creative destruction’ drives innovation and prosperity | Financial Times

From time to time, I vow not to read any more comments on the FT website. Trolls aside, I clearly live in a different universe. But then I return. It is indeed a signal-noise problem, but one in which the weighting has to be such that the fresh shoots are not overlooked. I know nothing about Paul A Myers, and I assume he lives in the US, but over the years you he has given me pause for thought on many occasions. One recent example below.

Comment from Paul A Myers

Science-based innovation largely comes out of the base of 90 research universities. One can risk an over-generalization and say there are no “universities” in a non-constitutional democratic country, or authoritarian regime. Engineering institutes maybe, but not research universities. Research is serendipity and quirky; engineering is regular and reliable. Engineering loves rules; research loves breaking them. The two fields are similar but worship at different altars.

This contrast is also true of medicine and science. Medicine is regulated to hell and back — badly, often — but I like my planes that way too. But, in John Naughton’s words, if you want great research, buy Aeron chairs, and hide the costs off the balance sheet lest the accountants start discounting all the possible futures.

Jonathan Flint · Testing Woes · LRB 6 May 2021

Terrific article from Jonathan Flint in the LRB. He is an English psychiatrist and geneticist (mouse models of behaviour) based in UCLA, but like many, has put his hand to other domains (beyond depression). He writes about Covid-19:

Perhaps the real problem is hubris. There have been so many things we thought we knew but didn’t. How many people reassured us Covid-19 would be just like flu? Or insisted that the only viable tests were naso-pharyngeal swabs, preferably administered by a trained clinician? Is that really the only way? After all, if Covid-19 is only detectable by sticking a piece of plastic practically into your brain, how can it be so infectious? We still don’t understand the dynamics of virus transmission. We still don’t know why around 80 per cent of transmissions are caused by just 10 per cent of cases, or why 2 per cent of individuals carry 90 per cent of the virus. If you live with someone diagnosed with Covid-19, the chances are that you won’t be infected (60 to 90 per cent of cohabitees don’t contract the virus). Yet in the right setting, a crowded bar for example, one person can infect scores of others. What makes a superspreader? How do we detect them? And what can we learn from the relatively low death rates in African countries, despite their meagre testing and limited access to hospitals?

That we are still scrambling to answer these questions is deeply worrying, not just because it shows we aren’t ready for the next pandemic. The virus has revealed the depth of our ignorance when it comes to the biology of genomes. I’ve written too many grant applications where I’ve stated confidently that we will be able to determine the function of a gene with a DNA sequence much bigger than that of Sars-CoV-2. If we can’t even work out how Sars-CoV-2 works, what chance do we have with the mammalian genome? Let’s hope none of my grant reviewers reads this.

Medicine is always messier that people want to imagine. It is a hotchpotch of kludges. For those who aspire to absolute clarity, it should be a relief that we manage effective action based on such a paucity of insight. Cheap body-hacks sometimes work. But the worry remains.

Tyler Cowen says some interesting things in an article Why Economics is Failing US on Bloomberg. I don’t think his comments are limited to the economics domain.

Why Economics Is Failing Us – Bloomberg

Economics is one of the better-funded and more scientific social sciences, but in some critical ways it is failing us. The main problem, as I see it, is standards: They are either too high or too low. In both cases, the result is less daring and creativity.

Consider academic research. In the 1980s, the ideal journal submission was widely thought to be 17 pages, maybe 30 pages for a top journal. The result was a lot of new ideas, albeit with a lower quality of execution. Nowadays it is more common for submissions to top economics journals to be 90 pages, with appendices, robustness checks, multiple methods, numerous co-authors and every possible criticism addressed along the way.

There is little doubt that the current method yields more reliable results. But at what cost? The economists who have changed the world, such as Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes or Friedrich Hayek, typically had brilliant ideas with highly imperfect execution. It is now harder for this kind of originality to gain traction. Technique stands supreme and must be mastered at an early age, with some undergraduates pursuing “pre-docs” to get into a top graduate school.

Sam Shuster, before I departed to Strasbourg, warned me in a similar vein, with reference to the Art of War by Sun Tzu:

Even the mystique of wisdom turns out to be technique. But if today must be learning technique, don’t leave the tomorrow of discovery too long.

I would say I heard the message but didn’t listen carefully enough. As befits an economist, Cowen warns us that there is no free lunch.

There was an article in the FT last week, commenting on an article in JAMA here. The topic is the use of AI (or, to be fair, other machine learning techniques) to help diagnose skin disease. Google will allow people to upload their own images and will, in turn, provide “guidance” as to what they think it is.

I think the topic important, and I wrote a little editorial on this subject here a few years ago with the strikingly unoriginal title of Software is eating the clinic. For about 8-10 years I used to work in this field but although we managed to get ‘science funding’ from the Wellcome Trust (and a little from elsewhere), and published extensively, we were unable to take it further via commercialisation. As is often the case, when you fail to get funded, you may not know why. My impression was that people did not imagine that there was a viable business model in software in this sort of area (we were looking for funds around 2012-2015). Yes, seemed crazy to me then, too (and yes, I know, Google have not proven there is a business model). Some of the answers via NHS and Scottish funding bodies were along the lines of come back when you prove it works, and then we will then fund the research.😤

A few days back somebody interested in digital health asked me what I thought about the recent work. Below is a lightly edited version of my email response.

- Long term automated systems will be used.

- Tumours will be easier than rashes.

- A rate-limiting factor is access to — and keeping — IPR of images.

- The computing necessary is now a commodity and trivial in comparison with images and annotation of images

- Regarding uncommon or odd presentations, computers are much more stupid than humans. Kids can learn what a table is with n<5 examples. Not so for machines. Trying to build databases of the ‘rare’ lesions will take a lot of time. It will only happen cheaply when the whole clinical interface is digital, ideally with automated total body image capture (a bit like a passport photo booth), and with metadata and the diagnosis added automatically.

- In the short term, the Google stuff will increase referrals. They are playing the usual ’no liability accepted, we are Silicon Valley, approach’. They say they are not making a diagnosis, just ‘helping’. This is the same nonsense as 23and me. They offload the follow-up onto medics / health service. Somebody once told me that some of the commercial ‘mole scanners’ sent every patient to their GP to further investigate — and refer on to hospital —their suspicious mole. This is a business model, not a health service.

- Geoffrey Hinton (ex Edinburgh informatics) who is one of the giants in this area of AI says in his talks that ‘nobody should train as a radiologist’. He is right and wrong. Yes, the error rate in modern radiology is very, very high — simply because they are reporting so many ‘slices’ in scans in comparison with old-fashioned single ‘films’ (e.g. chest X-ray). But single bits of tech in medicine are often in addition to what has previously happened rather that a replacement. In this domain, radiologists now do a lot more than just report films. So, you will still need radiologists but what they do will change. Humans are sentient beings and, given the right incentives, doctors are remarkably creative.

- There is still a very narrow perspective on skin disease in the UK, with a continued denial of the necessity for expertise. Primary care dermatology by doctors — let alone nurses who know even less and do not have professional registration in this domain of expertise — is a mess. It requires perceptual skills, and not unreasonably, many GPs do not have this because they have to know so much across a broad area of medicine. The average GP will see 1 melanoma every ten years. I started my dermatology training in Vienna: there are more dermatologists in Vienna than the whole of the UK. Specialism, pace Adam Smith and the pin factory, is what underpins much of the power of capitalism — and medicine, too. (Note: in this regard, some of the comparisons in the JAMA paper are facile).

- I think the machines will play a role and we are better with them than without them. But in the short term, demands on hospital practice will increase and waiting times will increase even further. This technology — in the short to medium term — will make things worse. At present, dermatology waiting times are worse than when I was a medical student (and this was true pre-Covid). You don’t need AI to know why.

If only we had been funded…. 😀. Only joking.

Originality is usually off track

How mRNA went from a scientific backwater to a pandemic crusher | WIRED UK

For decades, Katalin Karikó’s work into mRNA therapeutics was overlooked by her colleagues. Now it’s at the heart of the two leading coronavirus vaccines

By the mid 1990s, Karikó’s bosses at UPenn had run out of patience. Frustrated with the lack of funding she was generating for her research, they offered the scientist a bleak choice: leave or be demoted. It was a demeaning prospect for someone who had once been on the path to a full professorship. For Karikó’s dreams of using mRNA to create new vaccines and drugs for many chronic illnesses, it seemed to be the end of the road… ”It was particularly horrible as that same week, I had just been diagnosed with cancer,” said Karikó. “I was facing two operations, and my husband, who had gone back to Hungary to pick up his green card, had got stranded there because of some visa issue, meaning he couldn’t come back for six months. I was really struggling, and then they told me this.”

Karikó has been at the helm of BioNTech’s Covid-19 vaccine development. In 2013, she accepted an offer to become Senior Vice President at BioNTech after UPenn refused to reinstate her to the faculty position she had been demoted from in 1995. “They told me that they’d had a meeting and concluded that I was not of faculty quality,” she said. ”When I told them I was leaving, they laughed at me and said, ‘BioNTech doesn’t even have a website.’”

Being at the bottom of things

Donald Knuth is a legend amongst computer scientists.

I have been a happy man ever since January 1, 1990, when I no longer had an email address. I’d used email since about 1975, and it seems to me that 15 years of email is plenty for one lifetime.Email is a wonderful thing for people whose role in life is to be on top of things. But not for me; my role is to be on the bottom of things. What I do takes long hours of studying and uninterruptible concentration. I try to learn certain areas of computer science exhaustively; then I try to digest that knowledge into a form that is accessible to people who don’t have time for such study. [emphasis added]

On retirement:

I retired early because I realized that I would need at least 20 years of full-time work to complete The Art of Computer Programming (TAOCP), which I have always viewed as the most important project of my life.

Being a retired professor is a lot like being an ordinary professor, except that you don’t have to write research proposals, administer grants, or sit in committee meetings. Also, you don’t get paid.

My full-time writing schedule means that I have to be pretty much a hermit. The only way to gain enough efficiency to complete The Art of Computer Programming is to operate in batch mode, concentrating intensively and uninterruptedly on one subject at a time, rather than swapping a number of topics in and out of my head. I’m unable to schedule appointments with visitors, travel to conferences or accept speaking engagements, or undertake any new responsibilities of any kind.

On Keeping Your Soul

John Baez is indeed a relative of that other famous J(oan) Baez. I used to read his blog avidly

The great challenge at the beginning of ones career in academia is to get tenure at a decent university. Personally I got tenure before I started messing with quantum gravity, and this approach has some real advantages. Before you have tenure, you have to please people. After you have tenure, you can do whatever the hell you want — so long as it’s legal, and you teach well, your department doesn’t put a lot of pressure on you to get grants. (This is one reason I’m happier in a math department than I would be in a physics department. Mathematicians have more trouble getting grants, so there’s a bit less pressure to get them.)

The great thing about tenure is that it means your research can be driven by your actual interests instead of the ever-changing winds of fashion. The problem is, by the time many people get tenure, they’ve become such slaves of fashion that they no longer know what it means to follow their own interests. They’ve spent the best years of their life trying to keep up with the Joneses instead of developing their own personal style! So, bear in mind that getting tenure is only half the battle: getting tenure while keeping your soul is the really hard part. [emphasis added]

On the hazards of Epistemic trespassing

Scientists fear that ‘covidization’ is distorting research

Scientists straying from their field of expertise in this way is an example of what Nathan Ballantyne, a philosopher at Fordham University in New York City, calls “epistemic trespassing”. Although scientists might romanticize the role and occasional genuine insight of an outsider — such as the writings of physicist Erwin Shrödinger on biology — in most cases, he says, such academic off-piste manoeuvrings dump non-experts head-first in deep snow. [emphasis added]

But I do love the language…

On the need for Epistemic trespassing

Haack, Susan, Not One of the Boys: Memoir of an Academic Misfit

Susan Haack is a wonderfully independent English borne philosopher who loves to roam, casting light wherever her interest takes her.

Better ostracism than ostrichism

Moreover, I have learned over the years that I am temperamentally resistant to bandwagons, philosophical and otherwise; hopeless at “networking,” the tit-for-tat exchange of academic favors, “going along to get along,” and at self-promotion

That I have very low tolerance for meetings where nothing I say ever makes any difference to what happens; and that I am unmoved by the kind of institutional loyalty that apparently enables many to believe in the wonderfulness of “our” students or “our” department or “our” school or “our” university simply because they’re ours.

Nor do I feel what I think of as gender loyalty, a sense that I must ally myself with other women in my profession simply because they are women—any more than I feel I must ally myself with any and every British philosopher simply because he or she is British. And I am, frankly, repelled by the grubby scrambling after those wretched “rankings” that is now so common in philosophy departments. In short, I’ve never been any good at academic politicking, in any of its myriad forms.

And on top of all this, I have the deplorable habit of saying what I mean, with neither talent for nor inclination to fudge over disagreements or muffle criticism with flattering tact, and an infuriating way of seeing the funny side of philosophers’ egregiously absurd or outrageously pretentious claims — that there are no such things as beliefs, that it’s just superstitious to care whether your beliefs are true, that feminism obliges us to “reinvent science and theorizing,” and so forth.

.

Citizens of nowhere trespassing…

The Economist | Citizen of the world

From a wonderful article in the Economist

As Michael Massing shows vividly in “Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther and the Fight for the Western Mind” (2018), the growing religious battle destroyed Erasmianism as a movement. Princes had no choice but to choose sides in the 16th-century equivalent of the cold war. Some of Erasmus’s followers reinvented themselves as champions of orthodoxy. The “citizen of the world” could no longer roam across Europe, pouring honeyed words into the ears of kings. He spent his final years holed up in the free city of Basel. The champion of the Middle Way looked like a ditherer who was incapable of making up his mind, or a coward who was unwilling to stand up to Luther (if you were Catholic) or the pope (if you were Protestant).

The test of being a good Christian ceased to be decent behaviour. It became fanaticism: who could shout most loudly? Or persecute heresy most vigorously? Or apply fuel to the flames most enthusiastically?

And in case there is any doubt about what I am talking about.

In Britain, Brexiteers denounce “citizens of the world” as “citizens of nowhere” and cast out moderate politicians with more talent than they possess, while anti-Brexiteers are blind to the excesses of establishment liberalism. In America “woke” extremists try to get people sacked for slips of the tongue or campaign against the thought crimes of “unconscious bias”. Intellectuals who refuse to join one camp or another must stand by, as mediocrities are rewarded with university chairs and editorial thrones. [emphasis added]

As Erasmus might have said: ‘Amen’.

According to a helpful app on my phone that I like to think acts as a brake on my sloth, I retired 313 days ago. One of the reasons I retired was so that I could get some serious work done; I increasingly felt that professional academic life was incompatible with the sort of academic life I signed up for. If you read my previous post, you will see this was not the only reason, but since I have always been more of an academic than clinician, my argument still stands.

Over twenty years ago, my friend and former colleague, Bruce Charlton, observed wryly that academics felt embarrassed — as though they had been caught taking a sly drag round the back of the respiratory ward — if they were surprised in their office and found only to be reading. No grant applications open; no Gantt charts being followed; no QA assessments being written. Whatever next.

I thought about retirement from two frames of reference. The first, was about finding reasons to leave. After all, until I was about 50, I never imagined that I would want to retire. I should therefore be thrilled that I need not be forced out at the old mandatory age of 65. The second, was about finding reasons to stay, or better still, ‘why keep going to work?’. Imagine you had a modest private income (aka a pension), what would belonging to an institution as a paid employee offer beyond that achievable as a private scholar or an emeritus professor? Forget sunk cost, why bother to move from my study?

Many answers straddle both frames of reference, and will be familiar to those within the universities as well as to others outwith them. Indeed, there is a whole new genre of blogging about the problems of academia, and employment prospects within it (see alt-acor quit-lit for examples). Sadly, many posts are from those who are desperate to the point of infatuation to enter the academy, but where the love is not reciprocated. There are plenty more fish in the sea, as my late mother always advised. But looking back, I cannot help but feel some sadness at the changing wheels of fortune for those who seek the cloister. I think it is an honourable profession.

Many, if not most, universities are very different places to work in from those of the 1980s when I started work within the quad. They are much larger, they are more corporatised and hierarchical and, in a really profound sense, they are no longer communities of scholars or places that cherish scholarly reason. I began to feel much more like an employee than I ever used to, and yes, that bloody term, line manager, got ever more common. I began to find it harder and harder to characterise universities as academic institutions, although from my limited knowledge, in the UK at least, Oxbridge still manage better than most 1. Yes, universities deliver teaching (just as Amazon or DHL deliver content), and yes, some great research is undertaken in universities (easy KPIs, there), but their modus operandi is not that of a corpus of scholars and students, but rather increasingly bends to the ethos of many modern corporations that self-evidently are failing society. Succinctly put, universities have lost their faith in the primacy of reason and truth, and failed to wrestle sufficiently with the constraints such a faith places on action — and on the bottom line.

Derek Bok, one of Harvard’s most successful recent Presidents, wrote words to the effect that universities appear to always choose institutional survival over morality. There is an externality to this, which society ends up paying. Wissenschaft als Beruf is no longer in the job descriptions or the mission statements2.

A few years back via a circuitous friendship I attended a graduation ceremony at what is widely considered as one of the UK’s finest city universities3. This friend’s son was graduating with a Masters. All the pomp was rolled out and I, and the others present, were given an example of hawking worthy of an East End barrow boy (‘world-beating’ blah blah…). Pure selling, with the market being overseas students: please spread the word. I felt ashamed for the Pro Vice Chancellor who knew much of what he said was untrue. There is an adage that being an intellectual presupposes a certain attitude to the idea of truth, rather than a contract of employment; that intellectuals should aspire to be protectors of integrity. It is not possible to choose one belief system one day, and act on another, the next.

The charge sheet is long. Universities have fed off cheap money — tax subsidised student loans — with promises about social mobility that their own academics have shown to be untrue. The Russell group, in particular, traducing what Humboldt said about the relation between teaching and research, have sought to diminish teaching in order to subsidise research, or, alternatively, claimed a phoney relation between the two. As for the “student experience”, as one seller of bespoke essays argued4, his business model depended on the fact that in many universities no member of staff could recognise the essay style of a particular student. Compare that with tuition in the sixth form. Universities have grown more and more impersonal, and yet claimed a model of enlightenment that depends on personal tuition. Humboldt did indeed say something about this:

“[the] goals of science and scholarship are worked towards most effectively through the synthesis of the teacher’s and the students’ dispositions”.

As the years have passed by, it has seemed to me that universities are playing intellectual whack-a-mole, rather than re-examining their foundational beliefs in the light of what they offer and what others may offer better. In the age of Trump and mini-Trump, more than ever, we need that which universities once nurtured and protected. It’s just that they don’t need to do everything, nor are they for everybody, nor are they suited to solving all of humankind’s problems. As had been said before, ask any bloody question and the universal answer is ‘education, education, education’. It isn’t.

That is a longer (and more cathartic) answer to my questions than I had intended. I have chosen not to describe the awful position that most UK universities have found themselves in at the hands of hostile politicians, nor the general cultural assault by the media and others on learning, rigour and nuance. The stench of money is the accelerant of what seeks to destroy our once-modern world. And for the record, I have never had any interest in, or facility for, management beyond that required to run a small research group, and teaching in my own discipline. I don’t doubt that if I had been in charge the situation would have been far worse.

Reading debt

Sydney Brenner, one of the handful of scientists who made the revolution in biology of the second half of the 20th century once said words to the effect that scientists no longer read papers they just Xerox them. The problem he was alluding to, was the ever-increasing size of the scientific literature. I was fairly disciplined in the age of photocopying but with the world of online PDFs I too began to sink. Year after year, this reading debt has increased, and not just with ‘papers’ but with monographs and books too. Many years ago, in parallel with what occupied much of my time — skin cancer biology and the genetics of pigmentation, and computerised skin cancer diagnostic systems — I had started to write about topics related to science and medicine that gradually bugged me more and more. It was an itch I felt compelled to scratch. I wrote a paper in the Lancet on the nature of patents in clinical medicine and the effect intellectual property rights had on the patterns of clinical discovery; several papers on the nature of clinical discovery and the relations between biology and medicine in Science and elsewhere. I also wrote about why you cannot use “spreadsheets to measure suffering” and why there is no universal calculus of suffering or dis-ease for skin disease ( here and here ); and several papers on the misuse of statistics and evidence by the evidence-based-medicine cult (here and here). Finally, I ventured some thoughts on the industrialisation of medicine, and the relation between teaching and learning, industry, and clinical practice (here), as well as the nature of clinical medicine and clinical academia (here and here ). I got invited to the NIH and to a couple of AAAS meetings to talk about some of these topics. But there was no interest on this side of the pond. It is fair to say that the world was not overwhelmed with my efforts.

At one level, most academic careers end in failure, or at last they should if we are doing things right. Some colleagues thought I was losing my marbles, some viewed me as a closet philosopher who was now out, and partying wildly, and some, I suspect, expressed pity for my state. Closer to home — with one notable exception — the work was treated with what I call the Petit-mal phenomenon — there is a brief pause or ‘silence’ in the conversation, before normal life returns after this ‘absence’, with no apparent memory of the offending event. After all, nobody would enter such papers for the RAE/REF — they weren’t science with data and results, and since of course they weren’t supported by external funding, they were considered worthless. Pace Brenner, in terms of research assessment you don’t really need to read papers, just look at the impact factor and the amount and source of funding: sexy, or not?5

You have to continually check-in with your own personal lodestar; dead-reckoning over the course of a career is not wise. I thought there was some merit in what I had written, but I didn’t think I had gone deep enough into the problems I kept seeing all around me (an occupational hazard of a skin biologist, you might say). Lack of time was one issue, another was that I had little experience of the sorts of research methods I needed. The two problems are not totally unrelated; the day-job kept getting in the way.

The history of science is the history of rejected ideas (and manuscripts). One example I always come back to is the original work of John Wennberg and colleagues on spatial differences in ‘medical procedures’ and the idea that it is not so much medical need that dictates the number of procedures, but that it is the supply of medical services. Simply put: the more surgeons there are, the more procedures that are carried out1. The deeper implication is that many of these procedures are not medically required — it is just the billing that is needed: surgeons have mortgages and tuition loans to pay off. Wennberg and colleagues at Dartmouth have subsequently shown that a large proportion of the medical procedures or treatments that doctors undertake are unnecessary2.

Wennberg’s original manuscript was rejected by the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) but subsequently published in Science. Many of us would rate Science above the NEJM, but there is a lesson here about signal and noise, and how many medical journals in particular obsess over procedure and status at the expense of nurturing originality.

Angus Deaton and Anne Case, two economists, the former with a Nobel Prize to his name, tell a similar story. Their recent work has been on the so-called Deaths of Despair — where mortality rates for subgroups of the US population have increased3. They relate this to educational levels (the effects are largely on those without a college degree) and other social factors. The observation is striking for an advanced economy (although Russia had historically seen increased mortality rates after the collapse of communism).

Coming back to my opening statement, Deaton is quoted in the THE

The work on “deaths of despair” was so important to them that they [Deaton and Case] joined forces again as research collaborators. However, despite their huge excitement about it, their initial paper, sent to medical journals because of its health focus, met with rejections — a tale to warm the heart of any academic whose most cherished research has been knocked back.

When the paper was first submitted it was rejected so quickly that “I thought I had put the wrong email address. You get this ping right back…‘Your paper has been rejected’.” The paper was eventually published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, to a glowing reception. The editor of the first journal to reject the paper subsequently “took us for a very nice lunch”, adds Deaton.

Another medical journal rejected it within three days with the following justification

The editor, he says, told them: “You’re clearly intrigued by this finding. But you have no causal story for it. And without a causal story this journal has no interest whatsoever.”

(‘no interest whatsoever’ — the arrogance of some editors).

Deaton points out that this is a problem not just for medical journals but in economics journals, too; he thinks the top five economics journals would have rejected the work for the same reason.

“That’s the sort of thing you get in economics all the time,” Deaton goes on, “this sort of causal fetish… I’ve compared that to calling out the fire brigade and saying ‘Our house is on fire, send an engine.’ And they say, ‘Well, what caused the fire? We’re not sending an engine unless you know what caused the fire.’

It is not difficult to see the reasons for the fetish on causality. Science is not just a loose-leaf book of facts about the natural or unnatural world, nor is it just about A/B testing or theory-free RCTs, or even just ‘estimation of effect sizes’. Science is about constructing models of how things work. But sometimes the facts are indeed so bizarre in the light of previous knowledge that you cannot ignore them because without these ‘new facts’ you can’t build subsequent theories. Darwin and much of natural history stands as an example, here, but my personal favourite is that provided by the great biochemist Erwin Chargaff in the late 1940s. Wikipedia describes the first of his ‘rules’.

The first parity rule was that in DNA the number of guanine units is equal to the number of cytosine units, and the number of adenine units is equal to the number of thymine units.

Now, in one sense a simple observation (C=G and A=T), with no causal theory. But run the clock on to Watson and Crick (and others), and see how this ‘fact’ gestated an idea that changed the world.

- The original work was on surgical procedures undertaken by surgeons. Medicine has changed, and now physicians undertake many invasive procedures, and I suspect the same trends would be evident. ↩

- Yes, you can go a lot deeper on this topic and add in more nuance. ↩

- Their book on this topic is Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism published by Princeton Universty Press. ↩

There was a touching obituary of Peter Sleight in the Lancet. Sleight was a Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at Oxford and the obituary highlighted both his academic prowess and his clinical skills. Hard modalities of knowledge to combine in one person.

Throughout all this, at Oxford’s Radcliffe Infirmary and John Radcliffe Hospital, Sleight remained an expert bedside clinician, who revelled in distinguishing the subtleties of cardiac murmurs and timing the delays of opening snaps.

And then we learn

An avid traveller, Sleight was a visiting professor in several universities; the Oxford medical students’ Christmas pantomime portrayed him as the British Airways Professor of Cardiology. [emphasis added]

This theme must run and run, and student humour is often insightful (and on occasion, much worse). I worked somewhere where the nickname for the local airport was that of a fellow Gold Card professor. We often wondered what his tax status was.

From this week’s Economist | Breaking through

Yet nowhere too little capital is being channelled into innovation. Spending on R&D has three main sources: venture capital, governments and energy companies. Their combined annual investment into technology and innovative companies focused on the climate is over $80bn. For comparison, that is a bit more than twice the R&D spending of a single tech firm, Amazon.

Market and state failure may go together. Which brings me back to Stewart Brand’s idea of Pace Layering

Education is intellectual infrastructure. So is science. They have very high yield, but delayed payback. Hasty societies that can’t span those delays will lose out over time to societies that can. On the other hand, cultures too hidebound to allow education to advance at infrastructural pace also lose out.

Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning

I won’t even mention COVID-19.

Fail. Fail again. Fail better.

I came across a note in my diary from around fifteen years ago. It was (I assume) after receiving a grant rejection. For once, I sort of agreed with the funder’s decision1. I wrote:

My grant was trivial, at least in one sense. Neils Bohr always said (or words to the effect) that the job of science was to reduce the profound to the trivial. The ‘magical’ would be made the ordinary of the everyday. My problem was that I started with the trivial.

As for the merits of review: It’s the exception that proves the rule.

- Bert Vogelstein, who I collaborated with briefly in the 1990s, after seeing our paper initially rejected by the glossy of the day , informed me that the only sensible personal strategy was to believe that reviewers are always wrong. ↩

The background is the observation that babies born by Caesarian have different gut flora than those born vaginally. The interest in gut flora is because many believe it relates causally to some diseases. How do you go about investigating such a problem?

Collectively, these seven women gave birth to five girls and two boys, all healthy. Each of the newborns was syringe-fed a dose of breast milk immediately after birth—a dose that had been inoculated with a few grams of faeces collected three weeks earlier from its mother. None of the babies showed any adverse reactions to this procedure. All then had their faeces analysed regularly during the following weeks. For comparison, the researchers collected faecal samples from 47 other infants, 29 of which had been born normally and 18 by Caesarean section. [emphasis added]

‘Statisticians have already overrun every branch of science with a rapidity of conquest rivalled only by Attila, Mohammed, and the Colorado beetle’

Maurice Kendall (1942): On the future of statistics. JRSA 105; 69-80.

Yes, that Maurice Kendall.

It seems to me that when it comes to statistics — and the powerful role of statistics in understanding both the natural and the unnatural world — that the old guys thought harder and deeper, understanding the world better than many of their more vocal successors. And that is without mentioning the barking of the medic-would-be-statistician brigade.

I had forgotten this piece I wrote a few years back for Reto Caduff’s amazing book onFreckles. Here it is:

Imagine at some future time, two young adults meet on an otherwise deserted planet. They are both heavily freckled. What would this tell us about them, their ancestors and how they had have spent their time? First, all of us learn early in life that skin colour and marks like freckles are unequally distributed across the people of this earth. They are most common in people with pale skin, especially so if they have red hair, and we all know that we get our skin colour from our parents. Second, freckles are most common in those who have spent a lot of time in the sun. So freckles betray both something about our ancestors, and how we ourselves have lived our life.

Skin colour varies across the earth, and the chief determinant of this variation has been the interaction between sunshine (more particularly ultraviolet radiation) and our skin over the last 5 to 50 thousand years. Dark skin is adapted so as to protect against excessive sunshine, whereas we think light skin is better adapted to areas where the sun shines less. As some humans migrated out of Africa, say 50,000 years ago, a series of changes or mutations occurred in many genes to make their skin lighter. Their skin became more sensitive to both the good and the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation. One way this change was accomplished was the development of changes in a gene called the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), a gene we could also call a gene for freckles.

Skin and hair colour arises from a mixture of two types of the pigment melanin: brown or eumelanin, and red, or pheomelanin. If the MC1R works effectively, eumelanin is favoured; if the MC1R works less well, pheomelanin is favoured. We know that the change to pheomelanin is associated with skin that is more sensitive to sunshine. When people who harbour changes in MC1R are exposed to sun they are much more likely to develop freckles, than those who contain no changes in their MC1R.

And what about the freckles themselves? They are just tiny areas of melanin production. Ironically, to the best of our knowledge the freckles themselves seem to protect against the sun quite effectively. It is the non-freckled areas that are most sensitive to the sun. If in a bid to protect skin against the harmful effects of excessive sun, we were to join all the freckles up, the sensitivity might disappear. Of course, on a planet located far away in time and place, our two young adults might already possess the technology to join all their freckles together. It is just that they chose not to.

Many years ago I was expressing exasperation at what I took to be the layers and layers of foolishness that meant that others couldn’t see the obvious — as defined by yours truly, of course. Did all those wise people in the year 2000 think that gene therapy for cancer was just around the corner, or that advance in genetics was synonymous with advance in medicine, or that the study of complex genetics would, by the force of some inchoate logic, lead to cures for psoriasis and eczema. How could any society function when so many of its parts were just free-riding on error, I asked? Worse still, these intellectual zombies starved the new young shoots of the necessary light of reason. How indeed!

William Bains, he of what I still think of as one of the most beautiful papers I have ever read1, put me right. William understood the world much better than me — or at least he understood the world I was blindly walking into, much better. He explained to me that it was quite possible to make money (both ‘real’ or in terms of ‘professional wealth’) out of ideas that you believed to be wrong as long as two linked conditions were met. First, do not tell other people you believe them to be wrong. On the contrary, talk about them as the next new thing. Second, find others who are behind the curve, and who were willing to buy from you at a price greater than you paid (technical term: fools). At the time, I did not even understand how pensions worked. Finally, William chided me for my sketchy knowledge of biology: he reminded me that in many ecosystems parasites account for much, if not most, of the biomass. He was right; and although my intellectual tastes have changed, the sermon still echoes.

The reason is that corporate tax burdens vary widely depending on where those profits are officially earned. These variations have been exploited by creative problem-solvers at accountancy firms and within large corporations. People who in previous eras might have written symphonies or designed cathedrals have instead saved companies hundreds of billions of dollars in taxes by shifting trillions of dollars of intangible assets across the world over the past two decades. One consequence is that many companies avoid paying any tax on their foreign sales. Another is that many countries’ trade figures are now unusable. [emphasis added].

Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International by Matthew C. Klein, & Michael Pettis.

- William Bains. Should you Hire an Epistemologist. Nature Biotechnology, 1997. ↩

That “scientific management” bungled the algorithm for children’s exam results, verifies a maxim attributed to J.R. Searle, an American philosopher: if you have to add “scientific” to a field, it probably ain’t.

AD.Pellegrini in a letter to the Economist.

I have written elsewhere about this in medicine and science. We used to have physiology, but now some say physiological sciences; we used to have pharmacology, but now often see pharmacological sciences1. And as for medicine, neurology and neurosurgery used to be just fine, but then the PR and money grabbing started so we now have ‘clinical neuroscience’ — except it isn’t. As Herb Simon pointed out many years ago, the professions and professional practice always lose out in the academy.

- Sadly, my old department in Newcastle became Dermatological Sciences, and my most recent work address is Deanery of Clinical Sciences — which means both nouns are misplaced. ↩

“We’re going through a Copernican revolution of healthcare, where the patient is going to be at the centre. The gateway to healthcare is not going to be the physician. It’s going to be the smartphone.”…

and

“Christofer Toumazou, chief scientist at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering at Imperial College London, says there are “megabucks” to be saved by using technology and data to shift the focus of healthcare towards prevention.”

Ahem. I have been reading Seamus O’Mahony’s excellent Can Medicine be Cured in which he does a great job of following up on the crazy hype of big genetics from 20 year ago (and many other areas of sales masquerading as science). The above quotes are from only seven years ago. Still crazy after all these years, sings Paul Simon. Health care excels at adding tech as a new layer of complexity rather than replacing existing actors. And when will people start realising that prevention — which may indeed reduce suffering — will often increase costs. Life is a race against an army of exponential functions.

In the FT

Alas, there will no more new ones of these, as arguably the greatest of modern biology’s experimentalists, Sydney Brenner, passed away last year. One of his earlier quotes — the source I cannot find at hand — was that it is important in science to be out of phase. You can be ahead of the curve of fashion or possibly, better still, be behind it. But stay out of phase. So, no apologies for being behind the curve on these ones which I have just come across.

Sydney Brenner remarked in 2008, “We don’t have to look for a model organism anymore. Because we are the model organisms.”

Sydney Brenner has said that systems biology is “low input, high throughput, no output” biology.

Quoted in The science and medicine of human immunology | Science

Image source and credits via WikiCommons

More accurately, late night thoughts from 26 years ago. I have no written record of my Edinburgh inaugural, but my Newcastle inaugural given in 1994 was edited and published by Bruce Charlton in the Northern Review. As I continue to sift through the detritus of a lifetime of work, I have just come across it. I haven’t looked at it for over 20 years, and it is interesting to reread it and muse over some of the (for me) familiar themes. There is plenty to criticise. I am not certain all the metaphors should survive, and I fear some examples I quote from out with my field may not be as sound as I imply. But it is a product of its time, a time when there was some unity of purpose in being a clinical academic, when teaching, research and praxis were of a piece. No more. Feinstein was right. It is probably for the best, but I couldn’t see this at the time.

Late night thoughts of a clinical scientist

The practice of medicine is made up of two elements. The first is an ability to identify with the patient: a sense of a common humanity, of compassion. The second is intellectual, and is based on an ethic that states you must make a clear judgement of what is at stake before acting. That, without a trace of deception, you must know the result of your actions. In Leo Szilard’s words, you must “recognise the connections of things and the laws and conduct of men so that you may know what you are doing”.

This is the ethic of science. William Gifford, the 19th century mathematician, described scientific thought as “the guide of action”: “that the truth at which it arrives is not that which we can ideally contemplate without error, but that which we may act upon without fear”.

Late last year when I was starting to think what I wanted to say in my inaugural lecture, the BBC Late Show devoted a few programmes to science. One of these concerned itself with medical practice and the opportunities offered by advances in medical science. On the one side. Professor Lewis Wolpert, a developmental biologist, and Dr Markus Pembrey, a clinical geneticist, described how they went about their work. How, they asked, can you decide whether novel treatments are appropriate for a patient except by a judgement based on your assessment of the patient’s wishes, and imperfect knowledge. Science always comes with confidence limits attached.

On the opposing side were two academic ethicists, including the barrister and former Reith Lecturer Professor Ian Kennedy. You may remember it was Kennedy in his Reith lectures who quoting Ivan Illicit described medicine itself as the biggest threat to people’s health. The debate, or at least the lack of it. clearly showed that we haven’t moved on very far from when C P Snow (in the year I was born) gave his Two cultures lecture. What do I mean by two cultures? Is it that people are not aware of the facts of science or new techniques?… It was recently reported in the journal Science that over half the graduates of Harvard University were unable to explain why it is warmer in summer than winter. A third of the British population still believe that the sun goes round the earth.

But, in a really crucial way, this absence of cultural knowledge is not nearly so depressing as the failure to understand the activity rather the artefacts of science. Kennedy in a memorable phrase described knowledge as a ‘tyranny’1. It is as though he wanted us back with Galen and Aristotle, safe in our dogma, our knowledge fossilised and therefore ethically safe and neutered. There is, however, with any practical knowledge always a sense of uncertainly. When you lift your foot off the ground you never quite know where it is going to come down. And, as in Alice in Wonderland, “it takes all the running you can do to stay in the same place”.

It is this relationship, between practice and knowledge and how if affects my subject that I want to talk about. And in turn, I shall talk about clinical teaching and diagnosis, research and the treatment of skin disease.

Defining the appropriate probability space is often a non-trivial bit of statistics. It is often where you have to end up leaving statistics and formal reasoning behind. The following quote puts this in a more bracing manner.

There are no lobby groups for companies that do not exist.

The same goes for research and so much of what makes the future captivating.

Freeman Dyson died February 28th this year. There are many obituaries of this great mind and eternal rebel. His book, Disturbing the Universe, is for me one of a handful that gets the fundamental nature of discovery in science and how science interacts with other modes of being human. His intellectual bravery and honesty shine through most of his writings. John Naughton had a nice quote from him a short while back.

Some mathematicians are birds, others are frogs. Birds fly high in the air and survey broad vistas of mathematics out to the far horizon. They delight in concepts that unify our thinking and bring together diverse problems from different parts of the landscape. Frogs live in the mud below and see only the flowers that grow nearby. They delight in the details of particular objects, and they solve problems one at a time. I happen to be a frog, but many of my best friends are birds. The main theme of my talk tonight is this. Mathematics needs both birds and frogs.

In truth he was both frog and an albatross. Here are some words from his obituary in PNAS.

During the Second World War, Dyson worked as a civilian scientist for the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command, an experience that made him a life-long pacifist. In 1941, as an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge, United Kingdom, he found an intellectual role model in the famed mathematician G. H. Hardy, who shared two ideas that came to define Dyson’s trajectory: “A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns,” and “Young men should prove theorems; old men should write books.”

Heeding the advice of his undergraduate mentor, Dyson returned to his first love of writing. He became well-known to a wide audience by his books Disturbing the Universe (1979) (1) and Infinite in All Directions (1988) (2), and his many beautiful essays for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books. In 2018, he published his autobiography, Maker of Patterns (3), largely composed of letters that he sent to his parents from an early age on.

And as for us eternal students, at least I have one thing in common.

…Dyson never obtained an official doctorate of philosophy. As an eternal graduate student, a “rebel” in his own words, Dyson was unafraid to question everything and everybody. It is not surprising that his young colleagues inspired him the most.

Freeman J. Dyson 1923–2020: Legendary physicist, writer, and fearless intellectual explorer | PNAS

The beginning is where its at.

The best way to foster mediocrity is to found a Center for Excellence.

This is a quote from a comment by DrOFnothing on a good article by Rich DeMillo a few years back. It reminds me of my observation than shiny new research buildings often mean that the quality (but maybe not the volume) of reseach will deteriorate. This is just intellectual regression to the mean. You get the funding for the new building based on the trajectory of those who were in the old building — but with a delay. Scale, consistency and originality have a troubled relationship. Just compare the early flowerings of jazz-rock fusion (below) with the technically masterful but ultimately sterile stuff that came later.

The Nobel laureate David Hubel commented somewhere that reading most modern scientific papers was like chewing sawdust. Certainly it is rare nowadays to see the naked honesty of Watson and Crick’s classic opening paragraphs, or the melody not being drowned out by the the metrical percussion.

WE wish to suggest a structure for the salt of deoxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.). This structure has novel features which are of considerable biological interest [emphasis added].

A structure for nucleic acid has already been proposed by Pauling and Corey1. They kindly made their manuscript available to us in advance of publication. Their model consists of three intertwined chains, with the phosphates near the fibre axis, and the bases on the outside. In our opinion, this structure is unsatisfactory for two reasons : (1) We believe that the material which gives the X-ray diagrams is the salt, not the free acid. Without the acidic hydrogen atoms it is not clear what forces would hold the structure together, especially as the negatively charged phosphates near the axis will repel each other. (2) Some of the van der Waals distances appear to be too small.

And then there is that immortal understated penultimate paragraph.

It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.

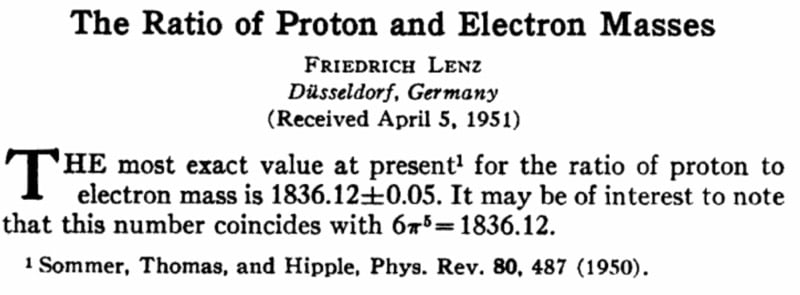

Well here is another one that impresses me even if I can claim no expertise in this domain. It is from the prestigious journal Physical Review, is 27 words in length, with one number, one equation and one reference. Via Fermat’s Library @fermatslibrary