Boeing, profit engineering and the destruction of value

Boeing: how not to run a national champion

The ongoing Boeing story (from the FT).

It’s not a surprise – late in life, even Welch realised that the focus on shareholder returns had been a mistake – or as he pithily put it “shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world” and that you build value for shareholders by building a good company and a good product.

Comment by BrassMonkey

Well this is what happens when you lay-off or demotivate a significant proportion of the layer of highly competent technical experts in a technology and manufacturing company. These Fellows and Senior Engineer meeting leads are the unsung glue that holds a business like Boeing on course. Ensuring it stays true to the well established aerospace principles while maintaining productivity and fighting the corner for technical professionalism against the onslaught of profit engineering . These seasoned experts ‘set the culture’ on the shop floors and ensured that it was maintained across B2B interfaces. Boeing has a serious problem of leaders that find their ways to the top who do not have technical or manufacturing backgrounds. This is in stark contrast to Airbus, where a significant number of their executive team have risen through the ranks building aircraft and factories. One sentence to sum up the whole problem. Top management don’t care about safety, they will cite “shareholder returns”, they don’t want to know about the issues just build lots of planes, do it quickly and make them cheap

Comment by Super Hank Petram

It’s not fixable. They have just appointed a new CEO-designate to succeed Calhoun. She is an accountant.

Medicine and health care is far, far, worse.

The desperate reality of a UK surgeon in Gaza

The desperate reality of a surgeon in Gaza

I came to understand why families without shelter cluster together when they are under attack, so they can live or die together.

NHS

The Notional Health Service.

Heading in last week’s Economist (13/1/2024). Sad, but true.

SLS: things that don’t appear in medic final’s

Which goes with that other common disease christened by the late Sydney Brenner (yes, the same Brenner): MDD or spelled out, money deficiency disease)

The Enlightened Economist | Economics and business books

The over-burdened welfare state is not quite coping with people suffering from what (I learned here) doctors describe as “Shit Life Syndrome” when they go to their GPs for help with depression or other mental ill-health conditions. And there will not be enough money to fix any of this unless growth picks up. But that would require a competent, effective government able to take clear decisions, build cross-party consensus, devolve money and powers, and stick with the plan without changing ministers and policies every 18 months.

Training? What training

Training is in tatters as doctors prioritise urgent care and discharges | The BMJ

“During my last job on an acute medical unit, one of the FY1s would sit in a box room separate from the doctor’s office for three days a week and write up to 15 discharge letters a day. It’s farcical to suggest that’s rounded training.”

…

“Prioritising training for juniors isn’t just about having competent and confident doctors in the NHS but actually having them at all. It’s hard to feel compelled to pursue a career in the NHS after a week in which your sole learning point was how to make the ward photocopier work,” she said.

Shopping for money

What supermarkets reveal about Britain’s economy

Last year a boss in the social-care sector told a parliamentary committee that he dreads hearing that an Aldi is opening nearby, as “I know I will lose staff.”

Timing

Rishi Sunak used helicopter for trip from London to Norwich | Rishi Sunak | The Guardian

Rishi Sunak has used a helicopter to travel to and from an engagement in Norwich, a trip of little more than 100 miles, Downing Street has confirmed, in another example of the prime minister’s fondness for flying brief distances.

UWE Bristol rugby player waited five hours for ambulance, inquest hears | Bristol | The Guardian

A 20-year-old university student who died after being injured in a rugby match and acquiring an infection in hospital lay in agony on the pitch for more than five hours while she waited for an ambulance, an inquest has heard.[she had a dislocated hip]

Patients in England will become the first in the world to benefit from a jab that treats cancer in seven minutes.

It is expected that the majority of these people will now get the drug via a seven-minute injection instead of intravenously, which usually takes 30 minutes to an hour.

How many months they wait to be seen, scanned or started off on treatment is not mentioned.

Don’t aim to work in the NHS

A little while back, Lisa and I were out for dinner at a friend’s house. The mother, ’M’ was a doctor and the husband, ‘H’, worked in finance. M ticked all the boxes for what you might wish for if you were a patient: technically competent, deeply caring, and worked way beyond her contractual hours. Nor did she park her patients in some tidy box somewhere: her job was part of who she was.

M and H had a few children under 11. As often happens, while watching the children play and interact, the question was asked what they might end up doing as a career. H spoke immediately and with conviction: ‘I just hope neither of them ever works for the NHS.’ Note, not I hope they do not become doctors, but rather I don’t want them ever working in the NHS.

I find it hard to imagine this same conversation a quarter-century ago. Things have changed.

Training is in tatters as doctors prioritise urgent care and discharges | The BMJ

“During my last job on an acute medical unit, one of the FY1s would sit in a box room separate from the doctor’s office for three days a week and write up to 15 discharge letters a day. It’s farcical to suggest that’s rounded training.”

…

“Prioritising training for juniors isn’t just about having competent and confident doctors in the NHS but actually having them at all. It’s hard to feel compelled to pursue a career in the NHS after a week in which your sole learning point was how to make the ward photocopier work,” she said.

A dog at the master’s gate predicts the ruin of the state. (William Blake)

Playing a corrupt signalling system

The ticking clock for America’s legacy admissions | Financial Times

This article from the FT is about Ivy league admissions in the USA but I think has relevance to the way people gain entry to medical schools in the UK. I was never involved in med student selection at either Newcastle or Edinburgh so I feel free to admit that I have always felt vaguely hostile to the grade 8 violin crowd. Now, self-taught guitarists, are another matter, as are those who have worked in paid employment whilst at school.

Many of us know at least one wealthy person whose kids spent a week in India or Tanzania building houses or digging latrines. Bizarrely, I know of a family that travelled to a nameless developing country on their private jet on precisely that quest. Competitive volunteering as a means of glamorising résumés for Ivy League applications long ago reached absurd heights. The ideal student would play concert-level violin, cure river blindness, win yachting competitions and get intensively coached into high SAT scores. At some point, the system has to collapse under the weight of its self-parody. I don’t know how close that moment is, or what a revolution in university admissions would precisely look like. But the data keeps pouring in.

Shit life syndrome

The Enlightened Economist | Economics and business books

The over-burdened welfare state is not quite coping with people suffering from what (I learned here) doctors describe as “Shit Life Syndrome” when they go to their GPs for help with depression or other mental ill-health conditions. And there will not be enough money to fix any of this unless growth picks up. But that would require a competent, effective government able to take clear decisions, build cross-party consensus, devolve money and powers, and stick with the plan without changing ministers and policies every 18 months.

As a med student I remember sitting in with an Irish senior registrar in psychiatry as he saw a young woman whose life seemed to consist of one random but state-induced tragedy after another. That she could still get out of bed and care for her numerous children seemed to me to attest both to her sanity and her moral character.

The psychiatrist’s assessment was blunt: the patient had no need of a physician, but needed to join the f***ing labour party and mobilise for office. Quite so.

More airline/pilot vs medicine/doctor metaphors

Cait Hewitt: ‘I hope the era of aviation exceptionalism is over’ | Financial Times

This year, the British government proudly unveiled an “ambitious” plan to make airports in England net zero by 2040. Only one problem: the target does not include the actual flights, which account for 95 per cent of airports’ emissions.

But Rishi Sunak’s government champions “guilt-free flying”: its so-called Jet Zero strategy is built on “ambitious” assumptions of future technology. Here Hewitt, mild-mannered, stretches to exasperation. “If you went to the doctor as a smoker, and said, ‘What shall I do?’ And the doctor said, ‘I think you should carry on with your 40-a-day habit, because I’m a very optimistic person, I believe in future there’s going to be some technology that will allow us to replace your lungs.’ Would you describe that person as ambitious or just completely reckless?”

Doctors, medicine and the NHS 1966

Like many of my colleagues I no longer try to dissuade my juniors from leaving to work in the United States. Medicine is more important than nationalism and will outlive the indifference of governments: it is better that a good man should work where he can make the best contribution to the advance of medicine than that he should stay to be frustrated by a society too myopic to appreciate his potential. A dead patient presents no economic problem.

It would be naive to express surprise at the equanimity with which successive governments have regarded the deteriorating hospital service, since it is in the nature of governments to ignore inconvenient situations until they become scandalous enough to excite powerful public pressure. Nor, perhaps, should one expect patients to be more demanding: their uncomplaining stoicism springs from ignorance and fear rather than fortitude; they are mostly grateful for what they receive and do not know how far it falls short of what is possible. It is less easy to forgive ourselves…..Indeed election as president of a college, a vice chancellor, or a member of the University Grants committee usually spells an inevitable preoccupation with the politically practicable, and insidious identification with central authority, and a change of role from informed critic to uncomfortable apologist.

Originally published in the Lancet, 1966,2, 647-54.(This version in Remembering Henry, edited by Stephen Lock and Heather Windle).

Henry Miller was successively Dean of Medicine, and VC of the University of Newcastle. No such present day post-holder would write with such clarity or honesty.

Governments can do it too.

Crypto-gram: June 15, 2023 – Schneier on Security

Now, tech giants are developing ever more powerful AI systems that don’t merely monitor you; they actually interact with you—and with others on your behalf. If searching on Google in the 2010s was like being watched on a security camera, then using AI in the late 2020s will be like having a butler. You will willingly include them in every conversation you have, everything you write, every item you shop for, every want, every fear, everything. It will never forget. And, despite your reliance on it, it will be surreptitiously working to further the interests of one of these for-profit corporations.

There’s a reason Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and other large tech companies are leading the AI revolution: Building a competitive large language model (LLM) like the one powering ChatGPT is incredibly expensive. It requires upward of $100 million in computational costs for a single model training run, in addition to access to large amounts of data. It also requires technical expertise, which, while increasingly open and available, remains heavily concentrated in a small handful of companies. Efforts to disrupt the AI oligopoly by funding start-ups are self-defeating as Big Tech profits from the cloud computing services and AI models powering those start-ups—and often ends up acquiring the start-ups themselves.

Yet corporations aren’t the only entities large enough to absorb the cost of large-scale model training. Governments can do it, too. It’s time to start taking AI development out of the exclusive hands of private companies and bringing it into the public sector. The United States needs a government-funded-and-directed AI program to develop widely reusable models in the public interest, guided by technical expertise housed in

I worry the UK government will sell all of the rights to NHS image libraries and raw patient data, rather than realise that the raw material is the gold dust. The models and tech will become a utility. Unless you steal, annotation of datasets is still the biggest expense ( the NHS considers it ‘exhaust’). Keep the two apart.

My disease is more important than your disease

Acute myeloid leukaemia – The Lancet

Acute myeloid leukaemia accounts for over 80 000 deaths globally per annum, with this number expected to double over the next two decades. The 5-year relative survival for patients in the USA diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia is currently 30·5%, improved from only 18% in the year 2000.5

Sometimes raw numbers — rather than rates — are appropriate. But not often. Instead, I suspect authors quote raw numbers to bolster ‘importance’. I have even see figures projected into the next quarter century. Why stop there, why not the next century?

In general and in this case the authors should have quote mortality rates. The standard, which usually works is per 100,000 of population. In the case, AML, a truly dreadful disease has a mortality rate of close to 1:100,000. The rate figure allows easy comparisons with other causes of death without having to check on the population numbers of the world population or other denominator.

It just bugs me. The Lancet is full of this sloppy editing. And how much of the projected increase is due to changes in the age structure of the world population? Yes, it all matters, but the frequent coupling of partisanship and hype needs a polite divorce.

2001 as metaphor

New Bayer chief plans a radically different style to cut bureaucracy | Financial Times

Anderson wants managers to overcome the traditional top-down approach and allow a team to develop a life of its own.

He likes to compare the situation of senior managers with that of the astronaut in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001 — A Space Odyssey”. In the science fiction movie, the scientists aboard a spaceship gradually find out that the computer had taken over the mission.

In one of his first meetings with Bayer managers, Anderson played a clip from the film. His message was that “the astronaut is us, and we are no longer in control” but at the same time, the system “often is fundamentally flawed”.

Which reminds me of the doctors and nurses stuck within the hull that is the NHS, directed in this case by the political masters who lack the guts to actually even set foot on the ship.

On discovering the truth

Daniel Ellsberg, Pentagon Papers whistleblower, dies aged 92 | US news | The Guardian

‘I’ve never regretted doing it’: Daniel Ellsberg on 50 years since leaking the Pentagon

In March, Ellsberg announced that he had inoperable pancreatic cancer. Saying he had been given three to six months to live, he said he had chosen not to undergo chemotherapy and had been assured of hospice care.

“I am not in any physical pain,” he wrote, adding: “My cardiologist has given me license to abandon my salt-free diet of the last six years. This has improved my life dramatically: the pleasure of eating my favourite foods!”

On Friday, the family said Ellsberg “was not in pain” when he died. He spent his final months eating “hot chocolate, croissants, cake, poppyseed bagels and lox” and enjoying “several viewings of his all-time favourite [movie], Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”, the family statement added.

He was 92….

Look up, not down

“in a mammoth bureaucracy obsessed with its own secrecy, the fault lines are best observed by those who, instead of peering down from the top, stand at the bottom and look up.“

Absolute Friends by John le Carré

True of the NHS.

The pleasure of electronic medical records

Digital Minimalism — An Rx for Clinician Burnout | NEJM

It’s easy to see how digital minimalism’s first tenet, “clutter is costly,” applies: the average patient’s EHR has 56% as many words as Shakespeare’s longest play, Hamlet. Moreover, half these words are simply duplicated from previous documentation.

Progress isn’t inevitable. Not even likely in some domains over working lifetimes.

Your rights are guaranteed, but not your teeth

Every child in the UK is entitled to free treatment by a nonexistent dentist. Some people on benefits, pregnant women and those who have recently given birth also have free and full access to an imaginary service. Your rights are guaranteed, up to the point at which you seek to exercise them.

It’s just business

The painfully high price of Humira is patently wrong | Financial Times

But nearly half of new drugs launched in the US in 2020-21 were priced at more than $150,000 a year, so others have followed its lead. An entire industry has moved towards making products that are breathtakingly expensive.

Please, please, start thinking about reining in IPR.

The Need for an Organised Ambulance Service in 1904.

I came across this article by chance while trying to track down same old papers on skin cancer. It was published in the Lancet in 1904. A few days ago I heard a story about a colleague’s problem in trying to order an ambulance for somebody having a MI.

It is remarkable how institutions can fail, and competence be something that now only exists in the past. This is not a difficult issue to solve. We no longer have a functioning health service. We have stepped back in time. But, hey, it only affects other people.

At an inquest held at Lambeth on nov. 21st Mr.Troutbeck inquired into the death of a girl, named Alice Wood,aged 17 years, of Camborne-road, Southfields, who died in a laundry van as she was being removed to st. Thomas’s hospital to undergo an operation for perforated gastric ulcer.

On Nov. 16th she complained of severe pain in the chest and about midnight Dr. E. A. Miller of Upper Richmond-road was called. He found the girl collapsed and, having diagnosed the condition, decided that an operation was her only chance. No cab could be obtained but at about 2A.M.on Nov.17th a laundry van was procured and in this she was driven to the hospital where on arrival she was found to be dead. Dr. L. Freyberger, who made the post-mortem examination, said that death was due to heart failure following acute peritonitis caused by the rupture of an internal ulcer and that it was accelerated by the jolting of the van. The coroner’s officer said that a horsed ambulance was kept at the Wandsworth Infirmary but that a relieving officer’s order was necessary for its use. The jury returned a verdict of “Death from natural causes,” and added a rider expressing the opinion that there was urgent need for an improvement in the system of providing horsed ambulances for the various metropolitan districts. With this we quite agree and we earnestly hope that the London County Council, which recently received a deputation from the Metropolitan Street Ambulance Association, will see its way to make proper provision.

Salve Lucrum: The Existential Threat of Greed in US Health Care

In the mosaic floor of the opulent atrium of a house excavated at Pompeii is a slogan ironic for being buried under 16 feet of volcanic ash: Salve Lucrum, it reads, “Hail, Profit.” That mosaic would be a fitting decoration today in many of health care’s atria.

The grip of financial self-interest in US health care is becoming a stranglehold, with dangerous and pervasive consequences. No sector of US health care is immune from the immoderate pursuit of profit, neither drug companies, nor insurers, nor hospitals, nor investors, nor physician practices.

Avarice is manifest in mergers leading to market concentration, which, despite pleas of “economies of scale,” almost always raise costs.

Yep. Don Berwick on fine form.

Politics and medicine

China’s Covid patients face medical debt crisis as insurers refuse coverage | Financial Times

Echoing Rudolf Virchow, frequent bedfellows. The spectrum includes the UK.

A doctor at Shanghai No 10 Hospital said staff had been instructed by the city’s health commission to limit Covid diagnoses. “We are advised to label most cases as respiratory infection,” the doctor said.

“What is certain is that the government can’t afford to treat everyone for free.”

China’s National Healthcare Security Administration said on Saturday that it would fully cover hospitalisation for Covid patients, but continued to exclude complications. Hospitals are also under pressure to reduce medical costs after the national insurance fund was strained by the costs of the sprawling zero-Covid apparatus.

In the eastern city of Hangzhou, Frank Wang, a marketing manager who bought a Covid insurance plan early last year, was refused proof of illness after he developed lung and kidney infections after testing positive for the virus.

“The hospital made it clear that Covid proof is not easy to obtain as the disease diagnosis has been politicised,” said Wang, who paid more than Rmb20,000 for treatment. “That makes patients like me a victim.”

The deserving and the undeserving sick redux; more crony capitalism.

Hugh Pennington | Deadly GAS · LRB 13 December 2022

Another terrific bit of writing by Hugh Pennington in the LRB. It is saturated with insights into a golden age of medical science.

Streptococcus pyogenes is also known as Lancefield Group A [GAS]. In the 1920s and 1930s, at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, Rebecca Lancefield discovered that streptococci could be grouped at species level by a surface polysaccharide, A, and that A strains could be subdivided by another surface antigen, the M protein.

Ronald Hare, a bacteriologist at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital in London, worked on GAS in the 1930s, a time when they regularly killed women who had just given birth and developed puerperal fever. He collaborated with Lancefield to prove that GAS was the killer. On 16 January 1936 he pricked himself with a sliver of glass contaminated with a GAS. After a day or two his survival was in doubt.

His boss, Leonard Colebrook, had started to evaluate Prontosil, a red dye made by I.G. Farben that prevented the death of mice infected with GAS. He gave it to Hare by IV infusion and by mouth. It turned him bright pink. He was visited in hospital by Alexander Fleming, a former colleague. Fleming said to Hare’s wife: ‘Hae ye said your prayers?’ But Hare made a full recovery.

Prontosil also saved women with puerperal fever. The effective component of the molecule wasn’t the dye, but another part of its structure, a sulphonamide. It made Hare redundant. The disease that he had been hired to study, funded by an annual grant from the Medical Research Council, was now on the way out. He moved to Canada where he pioneered influenza vaccines and set up a penicillin factory that produced its first vials on 20 May 1944. [emphasis added]

He returned to London after the war and in the early 1960s gave me a job at St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School. I wasn’t allowed to work on GAS. There wasn’t much left to discover about it in the lab using the techniques of the day, and penicillin was curative.

[emphasis added]

N of 1

Getting too deeply into statistics is like trying to quench a thirst with salty water. The angst of facing mortality has no remedy in probability.

Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air

Ain’t no rock’n roll star

Do you really want to live to be 100? | Financial Times

Sarah O’Connor in today’s FT

I’m one of life’s optimists. When I think about living to be 100 years old, I picture a birthday party where I am surrounded by my devoted descendants, perhaps followed by a commercial space flight as a celebratory treat.

But I’m in the minority here. A lot of people would rather be dead. In a recent UK poll by Ipsos, only 35 per cent of people said they wanted to become centenarians.

Unhappy doctors

Henry Marsh is a retired neurosurgeon who has lived an interesting life and who writes with great insight about the NHS and medicine. The following are from an interview in the Guardian.

Marsh retired from the NHS at the age of 65, after growing disenchanted with bureaucratic managers and his reduced surgical schedule. “I just got more and more frustrated,” he says. “Which is very sad because I believe deeply in the NHS. I think straying away from a tax-funded system is a terrible mistake.”

The final straw was a meeting in which Marsh was threatened by a senior manager with disciplinary action for wearing a tie on ward rounds. “That was the end as far as I was concerned,” he says. “Being threatened with disciplinary action by a fellow doctor because I was wearing a tie! That was too much.” He is concerned about the long-term prospects for the health service. “There are a lot of unhappy doctors around,” he says.

Been there: done that. “By a fellow doctor” sticks.

A dog at the master’s gate predicts the ruin of the state.

Very good article by Clare Gerada. Julian Tudor-Hart must be turning over in his grave.

‘In my 30 years as a GP, the profession has been horribly eroded’ | GPs | The Guardian

This last day was in many ways symptomatic of the changes I have seen over the course of 30 years. Today, with advances of medicines and technology, patients are living longer, often with three or even four serious long-term conditions, so having one patient with heart failure, chronic respiratory problems, dementia and previous stroke is not at all unusual, whereas 30 years ago the heart failure might have carried them off in their 60s. This makes every patient much more complex, and it can be much harder to manage them and to get the balance of treatments right.

Today, unlike 30 years ago, all patients are strangers and, as my catchment area now extends into different London boroughs, even the places I go are unfamiliar. Gone is the relationship between my community and me. Instead, I am part of a gig economy, as impersonal as the driver delivering a pizza. I ended the shift with a profound sense of loss and sadness.

I cannot help but think that as a society we have lost the ability to do many things that we once did moderately well. Things that often worked and were good.

Tidal waves from the GFC

Rana Foroohar In the FT

I have a dermatologist friend who recently sold his practice to a private equity firm, but couldn’t bear to stay on after because management forced him to cut the amount of time spent with patients in half, and focus more on scale and less on people…

Why does the idea of Leon Black or Stephen Schwarzman focusing on post-Covid health issues make me feel more depressed? Is healthcare going to become the new subprime, with surprise billing, crushing debt, and sub-par treatment? Our system is complicated and patchy as it is. But Peter, the larger issue is what I’d like your take on. Do you agree with folks who say that we’ve never left the great financial crisis? With debt at record levels, and the Federal Reserve about to raise rates significantly, where will you be looking for financial risk?

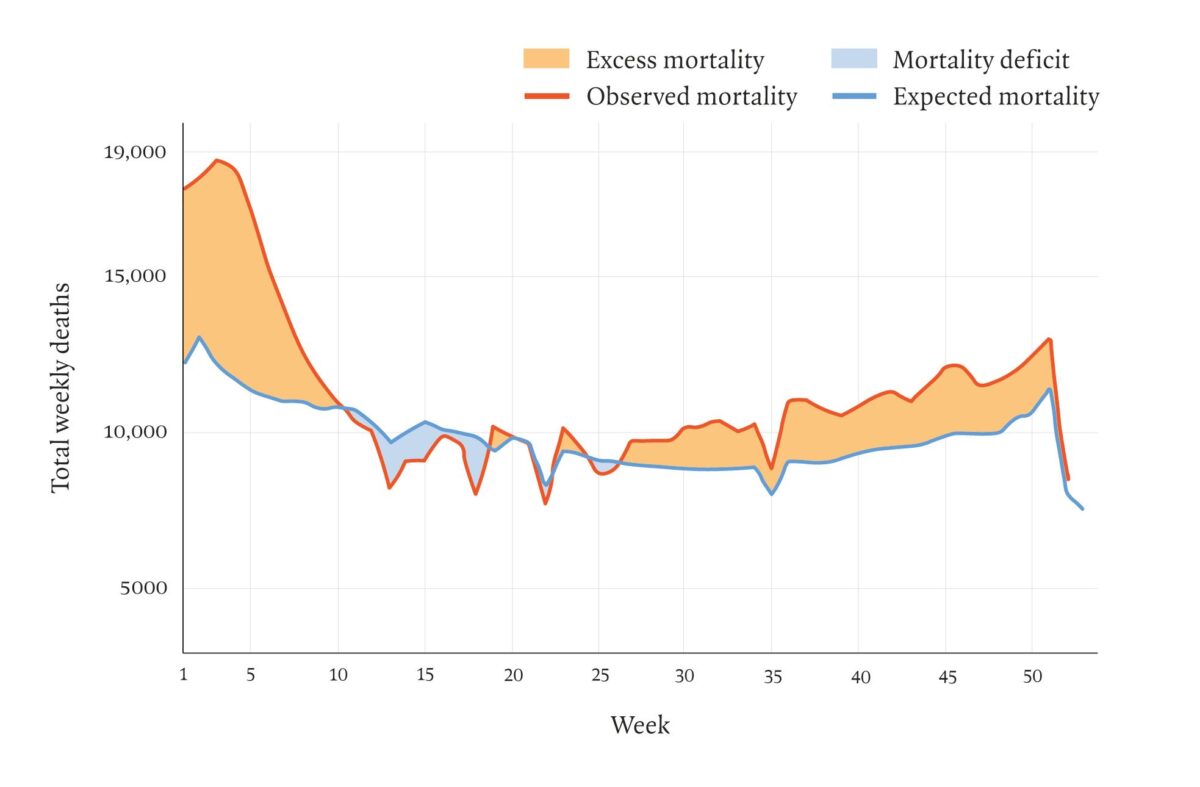

Excess deaths England & Wales 2021

Paul Taylor LRB 2002