Passwords

Awhile back the University of Edinburgh changed some of their guidance around passwords. In my 1Password app, I counted over 250 passwords. Some of these are old and no longer used, but the large number reflects the nature of academic life, in which information and knowledge flow is more outside the institution than within it. My bugbear is of course the NHS and the practice of making people remember hard passwords and change these passwords every 3-4 weeks. This is just bad practice, and leads to people writing them down close to where they use them, or choosing more guessable passwords. Another example of bad practice is below.

Slashdot asks if password masking — replacing password characters with asterisks as you type them — is on the way out. I don’t know if that’s true, but I would be happy to see it go. Shoulder surfing, the threat it defends against, is largely nonexistent — especially with personal devices. And it is becoming harder to type in passwords on small screens and annoying interfaces. The IoT will only exacerbate this problem, and when passwords are harder to type in, users choose weaker ones.

Turbotic teaching awards

“I’ve written extensively on the now famous Georgia Tech example of a tutorbot teaching assistant, where they swapped out one of their teaching assistants with a chatbot and none of the students noticed. In fact they though it was worthy of a teaching award”

- Donald Clark Plan B: Tutorbots are here – 7 ways they could change the learning landscape.

I keep reading this as ‘turbot’, and wondered what the fish things was. I guess the tutorbot would have corrected me soon enough.

Not so much split personality, but man-in-the-middle

Via Bruce Schneier:

The trouble began last year when he noticed strange things happening: files went missing from his computer; his Facebook picture was changed; and texts from his daughter didn’t reach him or arrived changed. “Nobody believed me,” says Gary. “My wife and my brother thought I had lost my mind. They scheduled an appointment with a psychiatrist for me.”

But he built up a body of evidence and called in a professional cybersecurity firm. It found that his email addresses had been compromised, his phone records hacked and altered, and an entire virtual internet interface created. “All my communications were going through a man-in-the-middle unauthorised server,” he explains.

Just one T-shirt away

This can be read as typical Silicon Valley hype, but I think it is more right than wrong. Just as government thought computer education in schools was about using MS Office, too many in higher education think it is about copies of dismal Powerpoints online, lecture capture, or online surveillance of students and staff. The computer revolution hasn’t happened yet. Medical education is a good place to start.

What can we do to accelerate the revolution? From our observation, the computer revolution is intertwined with the education revolution(and vice versa). The next steps in both are also highly overlapped: the computer revolution needs a revolution in education, and the education revolution needs a revolution in computing.

We think that, for any topic, a good teacher and good books can provide an above threshold education. For computing, one problem is that there aren’t enough teachers who understand the subject deeply enough to teach effectively and to guide children. Perhaps we can utilize the power of the computer itself to make education better? We don’t hope to be able to replace good teachers, but can the computer be a better teacher than a bad teacher?

Content matters

Interesting graphic from Audrey Watters on the bête noire, that is Pearson (especially if you are an investor). But although I think I am in a minority, I think universities are wrong to not understand how the world of content will impact on their business models. What is your content like, and what do you add to it? Content is key. But it doesn’t cost 9K, at least not if you scale it right.

Zuboff’s Laws

In the context of her research about the implications of information technology she stated three laws:

- Everything that can be automated will be automated.

- Everything that can be informated will be informated.

- Every digital application that can be used for surveillance and control will be used for surveillance and control.

Wikipedia. A lot of interesting links to her work. I never knew the origin.

Then we can call it computer engineering..

“If we are really going to turn over our homes, our cars, our health and more to private tech companies, on a scale never imagined,” he wrote, “we need much, much stronger standards for security and privacy than now exist. Especially in the US, it’s time to stop dancing around the privacy and security issues and pass real, binding laws.

“And, if ambient technology is to become as integrated into our lives as previous technological revolutions like wood joists, steel beams and engine blocks, we need to subject it to the digital equivalent of enforceable building codes and auto safety standards. Nothing less will do. And health? The current medical device standards will have to be even tougher, while still allowing for innovation.”

Nice piece on Walt Mossberg from John Naughton.

John Perry Barlow, revisited

Technology magnifies power in general, but the rates of adoption are different. Criminals, dissidents, the unorganized—all outliers—are more agile. They can make use of new technologies faster, and can magnify their collective power because of it. But when the already-powerful big institutions finally figured out how to use the Internet, they had more raw power to magnify.

This is true for both governments and corporations. We now know that governments all over the world are militarizing the Internet, using it for surveillance, censorship, and propaganda. Large corporations are using it to control what we can do and see, and the rise of winner-take-all distribution systems only exacerbates this.

This is the fundamental tension at the heart of the Internet, and information-based technology in general. The unempowered are more efficient at leveraging new technology, while the powerful have more raw power to leverage. These two trends lead to a battle between the quick and the strong: the quick who can make use of new power faster, and the strong who can make use of that same power more effectively.

Bruce Schneier, on Crooked Timber, talking around Cory Doctorow’s new novel ‘Walkaway’. BS—well worth reading in full, as usual.

Wannacry

Nice dissection of some of the issues by Ross Anderson, here.

And in today’s FT, we read

Microsoft held back from distributing a free repair for old versions of its software that could have slowed last week’s devastating ransomware attack, instead charging some customers $1,000 a year per device for protection against such threats.

Gee, a secure version of Windows? That’s extra.

As tech destroys jobs. And values.

If you want to explore the meme about tech destroying jobs (and value) there are some great quotes in a piece by Steven Levy about John Markoff, of the New York Times, stepping down. Some samples:

I used to tell people that the Times’ loyal readership was both its great strength and weakness. The good news was that they would read the paper until they died. The bad news was that they were dying.

Then when I went back to school one fall, the men were all gone. It was the fall of 1969 and the Union Bulletin had gone to offset type. The men in the aprons had vanished. They had been shipped off with the press to a small paper in Oregon. In their place were women in skirts working at Selectric keyboards.

The next transition happened 15 years later when I got my first job at a daily paper, the San Francisco Examiner. I was part of a new generation of reporters who went to the gym after work instead of the bar.

That’s another irony — that I was one of the first to write about the digital world, but when it really arrived it was pretty clear that I wasn’t going to be a digital native. When blogging began, John Dvorak told me that there was no point in doing it unless you posted at least seven times a day. “Why would I want to do that?” I thought. I had already worked for an afternoon daily and I never wanted to work for a wire service.

Some things won’t change. I’m certain that when the next corrupt president is impeached it will be because of the hard work and persistence of some new Woodward and Bernstein.

I have often quipped that high quality journalism could contribute more to health care in the UK than the Department of Health in London. This was once a daring proposition.

Ed tech 2016

From Audrey Watters excellent round up of the year that was:

I think it’s safe to say, for example, that venture capital investment has fallen off rather precipitously this year. True, 2015 was a record-breaking year for ed-tech funding – over $4 billion by my calculations. But it appears that the massive growth that the sector has experienced since 2010 stopped this year. Funding has shrunk. A lot. The total dollars invested in 2016 are off by about $2 billion from this time last year; the number of deals are down by a third; and the number of acquisitions are off by about 20%.

To the entrepreneur who wrote the Techcrunch op-ed in August that ed-tech is “2017’s big, untapped and safe investor opportunity.” You are a fool. A dangerous, exploitative one at that.

Lots of good reasons for this, but surely the main one is that the products are so awful. It is a big domain of human activity, although whether it is a market I will leave for the moment. But people may prefer to spend their money on something that works. And that is before we mention LMS. Of course we can just sell our students user data….

Lots more good stuff from her here, although a stiff drink may be seasonally appropriate.

The technocratic delusion

“This may upset some of my students at MIT, but one of my concerns is that it’s been a predominantly male gang of kids, mostly white, who are building the core computer science around AI, and they’re more comfortable talking to computers than to human beings. A lot of them feel that if they could just make that science-fiction, generalized AI, we wouldn’t have to worry about all the messy stuff like politics and society. They think machines will just figure it all out for us.”

Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab

(Via John Naughton)

Or as I quoted Steven Weinberg in a paper with the title, “The Problem with Academic Medicine: Engineering Our Way into and out of the Mess”

“My advice is to go for the messes—that’s where the action is.”

Enclosing not so much the commons, but space itself.

I first became ware of the importance of intellectual property law and custom after reading James Boyle’s ‘Shamans, Software and Spleens’. I had been completely unaware of how important the institution of private intellectual property was, and how destructive it frequently was of human advance. Of course, it was not meant to be this way. Boyle’s book is dense but funny, and he lambasts the contradictions in copyright law, the tortured logic in the bizarre attempts to explain why blackmail and insider trading are illegal, and the craziness that surrounded patenting DNA and what you can do with my spleen once you once removed it. As Cory Doctorow commented, about another of Boyle’s books, ‘Bound by Law’, “Copyright, a system that is meant to promote creativity, has been hijacked by a few industrial players and perverted. Today copyright is as likely to suppress new creativity as it is to protect it.” It was reading Boyle that led me to write an essay in the Lancet on how the ease or difficulty of assigning IPR distorted medical advance.

But this takes the ticket, I am quoting from Stephen Downes commenting on this:

This is a funny story with a surprise inside. The funny part is the artwork: an artist created glass blocks exactly the dimensions of a FedEx box and then shipped them in those boxes, producing unique art out of the cracks and breakage that resulted. The surprise is that it turns out that Fed Ex has corporate ownership over that space. “There’s a copyright designating the design of each FedEx box, but there’s also the corporate ownership over that very shape. It’s a proprietary volume of space, distinct from the design of the box.” Now I’m afraid I might accidentally violate FedEx’s ownership over that specific shape should I decide to, I don’t know, create my own mailing box.

Not so much enclosing the commons, but space itself.

Tim Wu: ‘The internet is like the classic story of the party that went sour’

educational fMRI and diagnosing cars with a thermometer over the bonnet

At the risk of raising the ire of many researchers, I should note that I am not basing my assessment on the rapid growth in educational neuroscience. You know, the kind of study where a subject is slid into an fMRI machine and asked to solve math puzzles. Those studies are valuable, but at the present stage, at best they provide at most tentative clues about how people learn, and little specific in terms of how to help people learn. (A good analogy would be trying to diagnose an engine fault in a car by moving a thermometer over the hood.) One day, educational neuroscience may provide a solid basis for education the way, say, the modern theory of genetics advanced medical practice. But not yet.

Keith Devlin, talking sense — again. I want to believe the the rest of the article but, worry it may not be so. But it contains some gems:

Classroom studies invariably end up as studies of the teacher as much as of the students, and often measure the effect of the students’ home environment rather than what goes on in the classroom.

This just adds to the problem that Geoff Norman (DOI 10.1007/s10459-016-9705-6) and others have talked about in course evaluations, namely that many studies — even accepting of the limitations outlines above — are riddled with pseudoreplication.

And:

What is missing is any insight into what is actually going on in the student’s mind—something that can be very different from what the evidence shows, as was dramatically illustrated for mathematics learning several decades ago

But, like many outwith medicine, I think he puts too much store by the robustness of the RCT approach — even with digital tools to allow large scale measurement. RCT: ‘randomised, confounded and trivial’, as has been said before (Norman).

Big data: more big money than big ideas

“Trouble is, the intrusions cannot be ignored or wished away. Nor can the coercion. Take the case of Aaron Abrams. He’s a math professor at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. He is covered by Anthem Insurance, which administers a wellness program. To comply with the program, he must accrue 3,250 “HealthPoints.” He gets one point for each “daily log-in” and 1,000 points each for an annual doctor’s visit and an on-campus health screening. He also gets points for filling out a “Health Survey” in which he assigns himself monthly goals, getting more points if he achieves them. If he chooses not to participate in the program, Abrams must pay an extra $50 per month toward his premium.

Abrams was hired to teach math. And now, like millions of other Americans, part of his job is to follow a host of health dictates and to share that data not only with his employer but also with the third-party company that administers the program. He resents it, and he foresees the day when the college will be able to extend its surveillance.”

Cathy O’Neil, ‘Weapons of Math Destruction’, excerpt on Backchannel.

This sort of thing is going to be all over education and our private lives. Big data masquerading as big ideas, or just ‘big money’. Its just because ‘we care’.

EdTech the Devil’s way.

Great post by Bryan Alexander, titled ‘ A Devil’s Dictionary of Educational Technology’. If you work in it, you will recognise it. I will start off with my favourites

Powerpoint, n. 1. A popular and low cost narcotic, mysteriously decriminalized.

YouTube, n. The ideal educational technology: everyone likes and uses it, it’s reliable and free, and neither you nor anyone you know has to support it.

Here are a few more:

Active learning , n. 1.The opposite of obedience lessons.

Asynchronous, adj. The delightful state of being able to engage with someone online without their seeing you, while allowing you to make a sandwich.

Best practice, n. “An educational approach that someone heard worked well somewhere. See also ‘transformative,’ ‘game changer,’ and ‘disruptive.’” (by Jim Julius)

LMS, n. 1) A document management system, whereby a faculty member can transfer a single document to his or her students. Curiously overpowered for this purpose, nevertheless universally deployed.

2) A good way to avoid legal notices about copyright.

3) The graveyard of pedagogical intentions. A sump for IT budgets.

Nice procrastination piece, or reality check, depending on whether you teach or you deliver teaching.

Edtech redux

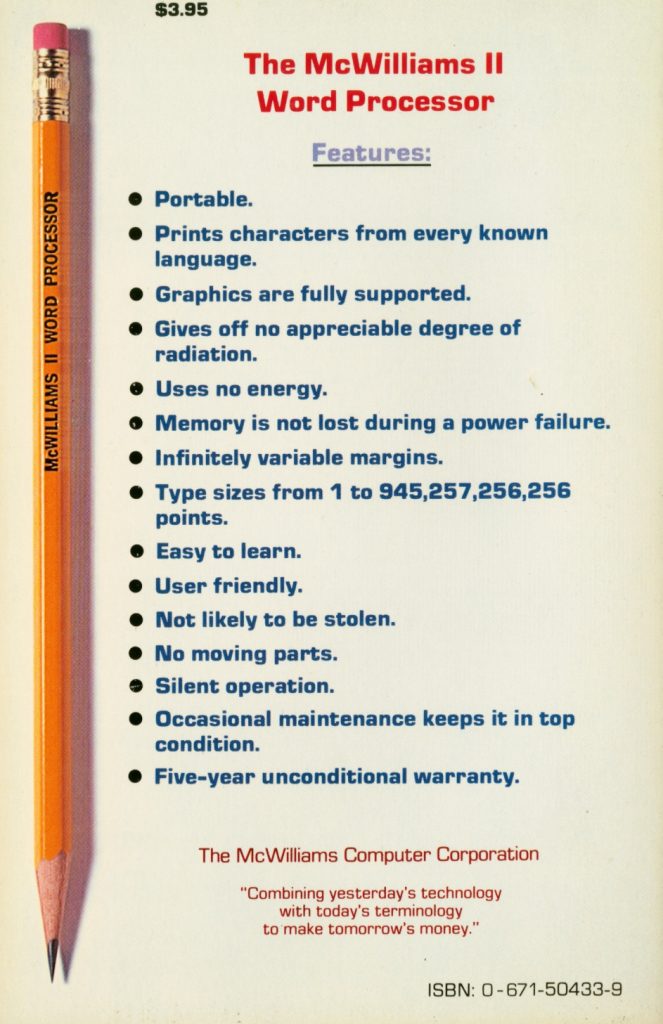

Blackboards, school buses, Nissen huts, and the pencil (via John Naughton, with original link here). Sadly, you have to invest time and effort in learning how to use it — so little to recommend to the multitaskers

We don’t need no teachers

‘People pay a lot for a great education now, but you can become expert level on most things by looking at your phone.’

Sam Altman quoted in the New Yorker

It is just nice to see it in black and white. So simple. BTW, the quote came via the wiser (not ‘smarter’) Nick Carr, who commented: ‘By “a really good life,” Altman means a virtual reality headset and an opioid prescription’.

Techno-pessimism, MOOCs and market failure in med ed

Attention: Some slipping of the causal nexus is evident.

An article in the Economist reviewing, or at least discussing, a couple of books about the rate of innovation caught my eye, in particular a snippet that I will expand on below. The books were “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” by Robert Gordon, and the “The Innovation Illusion” by Fredrik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel. I haven’t read either, but enjoyed a review of the Gordon book in the NYRB by Willian Nordhaus. Based on my reading of the Nordhaus book review the issue is that the rate of innovation and productivity is declining — we are not hurtling towards any singularity — and that the century of out of the ordinary innovation was 1870 to 1970. Here is Nordhaus:

Gordon focuses on growth in the United States. Living standards, as measured by GDP per capita or real wages, accelerated after 1870. The growth rate looks like an inverted U. Productivity growth rose from the late nineteenth century and peaked in the 1950s, but has slowed to a crawl since 1970. In designating 1870–1970 as the special century, Gordon emphasizes that the period since 1970 has been less special. He argues that the pace of innovation has slowed since 1970 (a point that will surprise many people), and furthermore that the gains from technological improvement have been shared less broadly (a point that is widely appreciated and true).

In the Economist article, we read:

The figures from recent years are truly dismal. Karim Foda, of the Brookings Institution, calculates that labour productivity in the rich world is growing at its slowest rate since 1950. Total factor productivity (which tries to measure innovation) has grown at just 0.1% in advanced economies since 2004, well below its historical average.

I do not find this view strange. Medical advance is slowing, not accelerating. Medicine was transformed between 1940 and 1970, but the rate of new discovery has slowed. There is more data , more activity, and more scientists, of course. And a lot more hype and university press officers. Just less advance in comparison with what went before. The same is true about university education, too.

Criticisms of these views include questions about the data used to support the various arguments. In the Economist piece, the ‘techno optimists’ make two criticisms. The second is that the ‘techno’ revolution hasn’t really started yet, but it is the first one that caught my eye:

The first is that there must be something wrong with the figures. One possibility is that they fail to count the huge consumer surplus given away free of charge on the internet. But this is unconvincing. The official figures may well be understating the impact of the internet revolution, just as they downplayed the impact of electricity and cars in the past, but they are not understating it enough to explain the recent decline in productivity growth.

Paul Mason elsewhere uses the example of Wikipedia:

Wikipedia is a non-market form of activity—it’s a $3bn hole in the advertising world.

Now bringing this back to my own little world, I am intrigued by how the battle between, on the one hand, free or OER, and on the other, books or content, you have to pay for, will work out. I touched on this in an article on teaching and learning several years ago, and one of the reasons I wrote the freely accessible textbook of skin cancer, www.skincancer909.com* was out of frustration at the poor quality of dermatology textbooks targeted at medical students. When I surveyed medical students a large fraction did not buy a dermatology textbook, yet it is clear that the university did not provide suitable alternatives, nor was the university able to provide reasonable online alternatives. Now, I do not believe that free is always best, nor do I think that the endgame is anytime soon. But I do believe content is critical, and despair at how the med ed (medical education) world largely ignores it. But there are amazing commercial books out there — think Molecular Biology of the Cell for instance — and there is a battle to be waged about whether you invest large amounts of money in producing material used by many, or continue with the traditional approach taken by universities (those ‘bloody PowerPoints’ and dull lectures, all done on a shoestring budget).

Woodie Flowers touched on cognate issues in a critique of MOOCs and MITx

In the United States, our “education” system is choking to death on a failed training system. Each year, 600,000 first-year college students take calculus; 250,000 fail. At $2000/failed-course, that is half-a-billion dollars. That happens to be the approximate cost of the movie Avatar, a movie that took a thousand people four years to make. Many of those involved in the movie were the best in their field. The present worth of losses of $500 million/year, especially at current discount rates, is an enormous number. I believe even a $100 million investment could cut the calculus failure rate in half.

The criticism stings because Flowers is an educational legend (it also speaks to MIT that they broadcast such critiques of their own activities). Here is Flowers again:

Properly designed new media materials can improve K–12, residential, distance, and life-long learning. In their highly developed form, these learning materials would be as elegantly produced as movies and video games and would be as engaging as a great novel.

I do not know how all of this will work out. I am intrigued by the view that we might be underestimating ‘production’ because much of it is free, but I think we are seeing real market failure, both from the commercial world and from the universities.

* Skincancer909 is due an update, and I am aiming for early 2017.

Two good things

First of all a link to an interview with Joe Ito and Barack Obama. The latter you may have heard about, but Ito is the head of the MIT media lab. Interesting, in that he has no higher ed qualifications. But then again, Jacob Bronowski, was deemed ineligible for a Chair in the UK because he appeared on the radio and TV. But can you really imagine this sort of thing from the bunch of tyros we call a UK government?

The second, an example of how sometimes it seems that scholarship is more in evidence on the web than within the walls of the academy. You think you understand the scurvy story, or how medical progress happens. Read on.

Edtech, Edinburgh and the blackboard.

“In the early 1800s, slate blackboards represented change. For centuries, students had used handheld tablets of wood or slate. Teachers moved about their classrooms, writing instructions and inspecting students’ work on individual slates. When the Scottish educational reformer James Pillans became the rector of Edinburgh High School, in 1810, his use of a blackboard was revolutionary. He explains in an 1856 memoir, Contributions to the Cause of Education:

I placed before my pupils, instead of a crowded and perplexing map, a large black board, having an unpolished non-reflecting surface, on which was inscribed in bold relief a delineation of the country, with its mountains, rivers, lakes, cities, and towns of note. The delineation was executed with chalks of different colours.

Widely recognized as the inventor of the blackboard, Pillans doesn’t specify how he constructed the apparatus……Pillans used his innovation to teach Greek as well as geography, noting,

The very novelty of all looking on one board, instead of each on his own book, had its effect in sustaining attention.”

Sounds familiar.

Distance learning and the unbundling of education approaches its 200th birthday

Interesting post from Tony Bates on the history of distance learning, and the University of London External Programme, which started in 1828.

Unfortunately I have no knowledge of the individuals who originally created the University of London External Programme back in 1828. It’s a worthy research project for anyone interested in the history of distance education.

I was once (mid-1960s) a correspondence tutor for students taking undergraduate psychology courses in the External Programme. In those days, the university would publish a curriculum (a list of topics) and provide a reading list. Students could sit an exam when they felt they were ready. Students paid tutors such as myself to help them with their studies. I would find old exam papers for the course, and set questions for individual students, and they would send me their answers and I would mark them. Many students were in British Commonwealth countries and it could take weeks after students sent in their essays before my feedback eventually got back to them. Not surprisingly, in those days completion rates in the programme were very low…

But I am fascinated by (and was ignorant of) the following:

Note though that teaching and examining in the original External Programme were disaggregated (those teaching it were different from those examining it), contract tutors were separate from the main faculty were used, and students studied individually and took exams when ready. So many of the ‘new’ developments in distance education such as disaggregation, self-directed learning, and many of the elements of competency-based learning are in fact over 150 years old.

Someone Is Learning How to Take Down the Internet

“Over the past year or two, someone has been probing the defenses of the companies that run critical pieces of the Internet. These probes take the form of precisely calibrated attacks designed to determine exactly how well these companies can defend themselves, and what would be required to take them down. We don’t know who is doing this, but it feels like a large a large nation state.”

Bruce Schneller (the ‘security guru’ in the words of the Economist) at Lawfare. You use it. And it is quite possible. Worth a read in full.

“I actually believe that we need domain specific online learning environments that cater to the pedagogies appropriate to different disciplines.” Mark Smithers

As compared with the LMS as all about management and and not much about learning.

Big data exceptionalism

This comment (and phrase) from Bruce Schneier struck a chord with me.

NYU professor Helen Nissenbaum gave an excellent lecture at Brown University last month, where she rebutted those who think that we should not regulate data collection, only data use: something she calls “big data exceptionalism.” Basically, this is the idea that collecting the “haystack” isn’t the problem; it what is done with it that is………Under this framework, the problem with wholesale data collection is not that it is used to curtail your freedom; the problem is that the collector has the power to curtail your freedom. Whether they use it or not, the fact that they have that power over us is itself a harm.

Of course, as Alan Kay said, we need ‘big ideas’ rather than assuming ‘big data’ will do our thinking for us. This is not to deny that large data sets are not useful, nor that they do not allow you to answer questions, you might not have been able to do so before. But A/B testing only gets you so far. And beware technicians who want to mould nature to their method, not vice versa; or change what meaningful consent means.

Textbooks: easy money

‘The rising prices of textbooks appears to be reaching a tipping point, the professor adds. The latest US Census Bureau statistics show that textbook prices increased more than 800 per cent from 1978 to 2014, more than triple the cost of inflation and more than the rate of increase of college tuition.’

Every Episode of David Attenborough’s Life Series, Ranked

Nice paean to David Attenborough, with the above title. There was a time when it is said that people like Jacob Bronowski were denied academic advance in the UK because he has appeared on TV. How the world of impact has changed. But just as many of us get excited by the power of the web to broaden access and change higher-ed, we should remember that some of the most potent educational agents of the twentieth century, got there before us. I am thinking cheap paperbacks (Pelican); the BBC; the OU on the BBC; and the movement throughout the 1930’s and beyond for prominent academics to reach out to that large part of the population who had been denied access to higher ed. If we want to build large scale resources for higher ed, we could do worse than look at the extraordinary teams the BBC put together. So, please don’t start lectures with those dismal learning outcomes, but just look at how Bond movies grab the attention and focus of their audience. Or just look at the Ascent of Man.

The best camera in the world is…

And not just because you have it in your pocket. Sean Baker has filmed a whole movie about ‘two miniskirted transgender prostitutes on the hunt for a woman who’s had an affair with one of their pimps’ with ‘just’ an iPhone. Below is an image my daughter Elizabeth Rees took, again, just with an iPhone. The subject matter is not the same, the father would add.